Energy Transport and Momentum Transport of EM Waves

Energy Transport

A characteristic property of waves is that they transport energy rather than mass. It is this energy which we typically detect with the help of a photodetector and not the electric field. We therefore need a quantity that describes this energy transport. From electrostatics, we know that that the energy density of the electric field is given by

To obtain such a quantity we recall the energy density of the electric and magnetic field which in sum give

Using the relation between the electric and the magnetic field amplitude we can further simplify the above expression for electromagnetic waves to

Let’s assume that we look at a volume

the integral over the time derivate of the energy density

where

We thus obtain the continuity equation

under vacuum conditions, meaning that we have no free charges and no charge current density.

We may use this equation to calculate the energy current density

We may simplify that expression with the help of Maxwell’s euqations

and the

Using the vector identity

we find

which is valid for vacuum and our energy current density can be identified as

The vector

This equation is known as Poynting theorem and just a way of writing energy conservation.

Let’s have a closer look at the Poynting vector, which we can write with the help of the magnetic flux density

The magnitude of the Poynting vector is then given by

which is the same as the intensity. The magnitude of the Poynting vector describes the intensity of an electromagnetic wave or the energy flow through an area. It therefore has the unit of an intensity, which is

If we now have a plane wave

in the real value description, then its intensity is

at a position

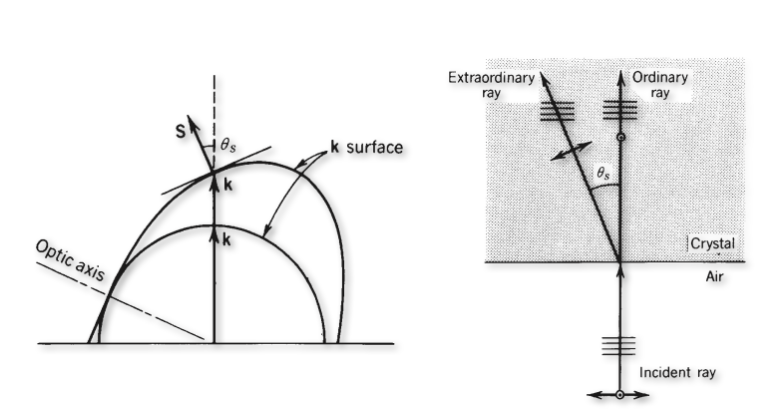

This is the intensity we would record with the help of a detector and the flow of energy is set by the direction of the Poynting vector. This is not to be confused with the flow of the wavefronts, which go in the direction of the wavevector.

An example where this happens are birefringent materials, where the wavefronts and the Poynting vector are not parallel to each other. In this case the energy flow is not in the direction of the wavefronts. This is a very important concept in optics, as it is the energy flow that is important for the heating of materials and not the direction of the wavefronts.

Momentum Transport and Radiation Pressure

Like the energy of a wave that can be transfered to objects like photodetectors, elecromagnetic waves also transport momentum, which can be turned into a motion of objects, when waves collide with massive objects. The momentum is a property of the electromagnetic wave. We would like to describe that so-called radiation pressure (the flow of momentum through an area) in a very simple way.

For this purpose we need he relativistic energy

which can be calculated from the momentum

Therefore the momentum density in a volume must be also equal to the energy density devided by the speed of light.

Therefore the momentum density

The momentum that is therfore transported through an area

since the volume from which the momentum comes is

As

So far, this is a hypothetical radiaton pressure, which we relate to the flow of momentum. It becomes a real pressure, if the radiation interacts with some surface.

If we consider a perfectly absorbing surface of area

is the radiation pressure for perfect absorption.

If we have, however, a perfectly reflecing surface, we transfer due to the reflection, twice the momentum to the wall and therefore teh radiaton pressure for perfect reflection is

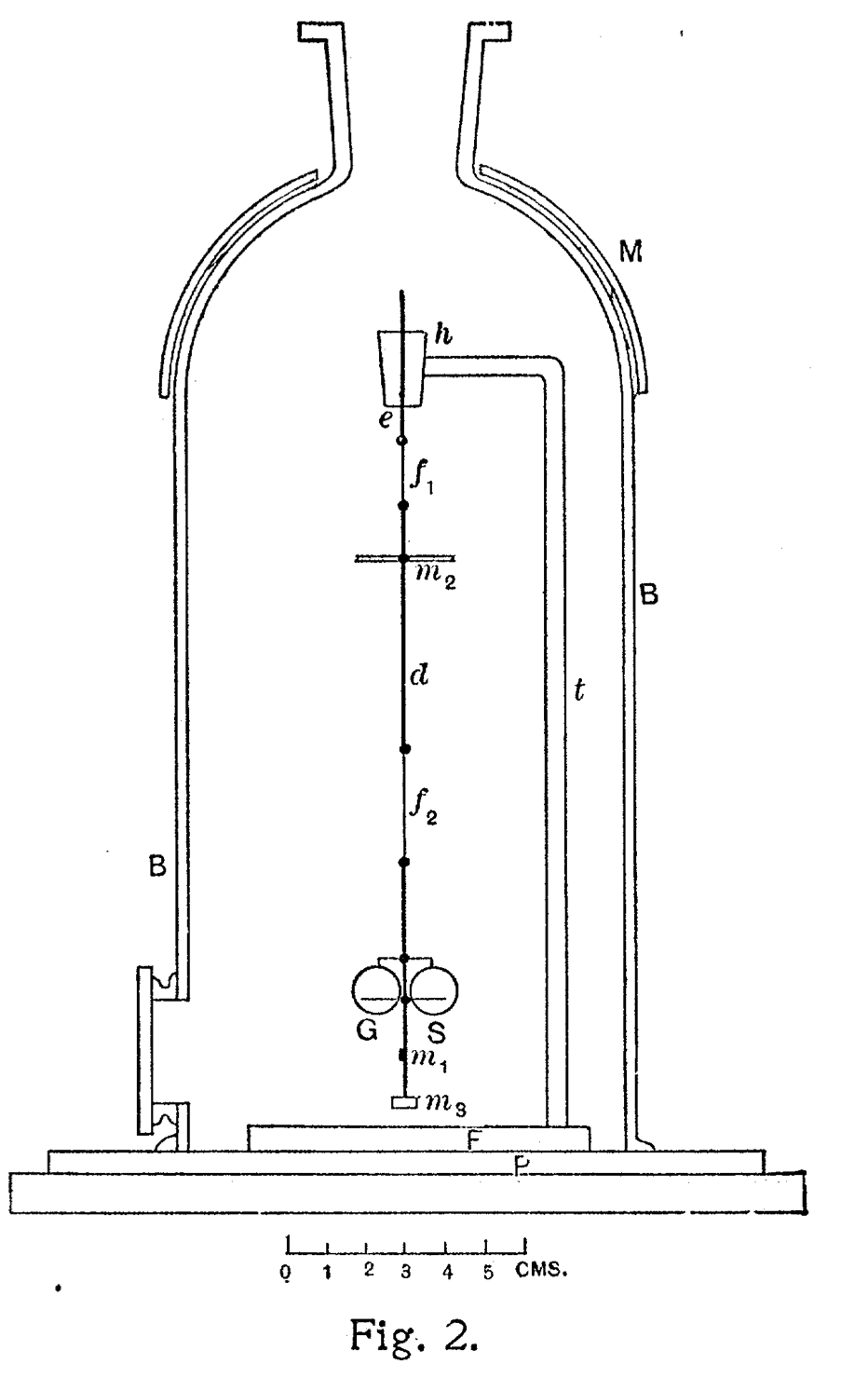

Thus if you want to measure radiation pressure, its best to use reflecting surfaces. This has been done for the first time in an experiment by Nichols and Hull in the years from 1900-1903.

Radiation Pressure measurements

Nichols and Hull mounted therefore the two mirrors on a torsion spring in a geometry much like the Cavendish experiment. The light falling on both mirrors creates tiny forces which elongate the torsionspring which is mounted in a vessel where air is removed. From the elongation one may determine the forces and thus the pressure. From a separate measurement of the absorption and conversion of light into heat (with a Boulometer), one can deermine the intensity or energy contained in the radiation.

Comet Tails

Radiation pressure is also of importance in astronomy and in particular visible in the tail of comets. Comets show tails composed of light gas ions and dust particles which seperate under the influence of radiation pressure. While orbiting around a star, the radiation pressure pushes the ligh gas ions radially away from the star, while the dust particles follow a curved shape ben towards the orbit due to their larger mass. This is also visible in the photograph we took in July 2020 for the comet Neowise which passed earth in a very spectacular way.

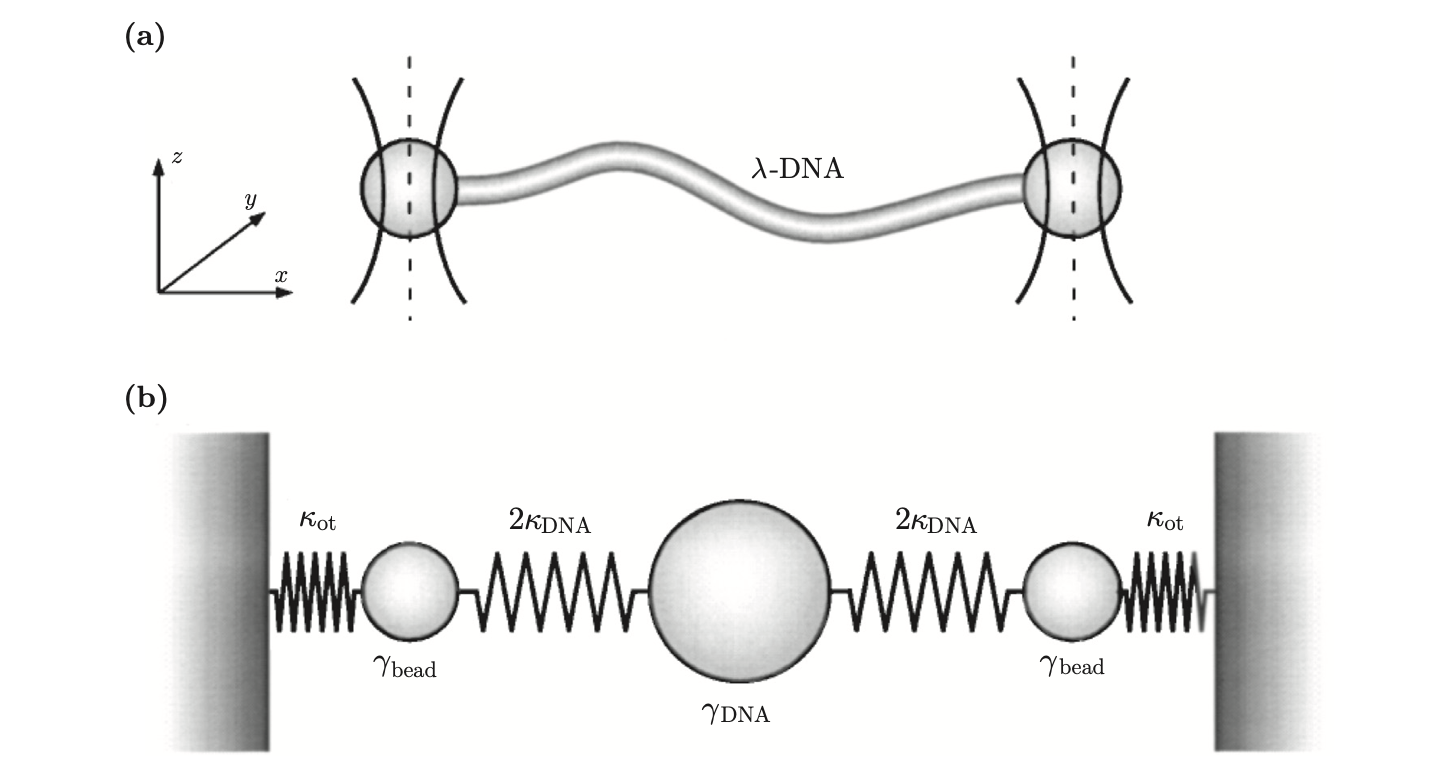

Optical Tweezers and Magneto-optical Traps

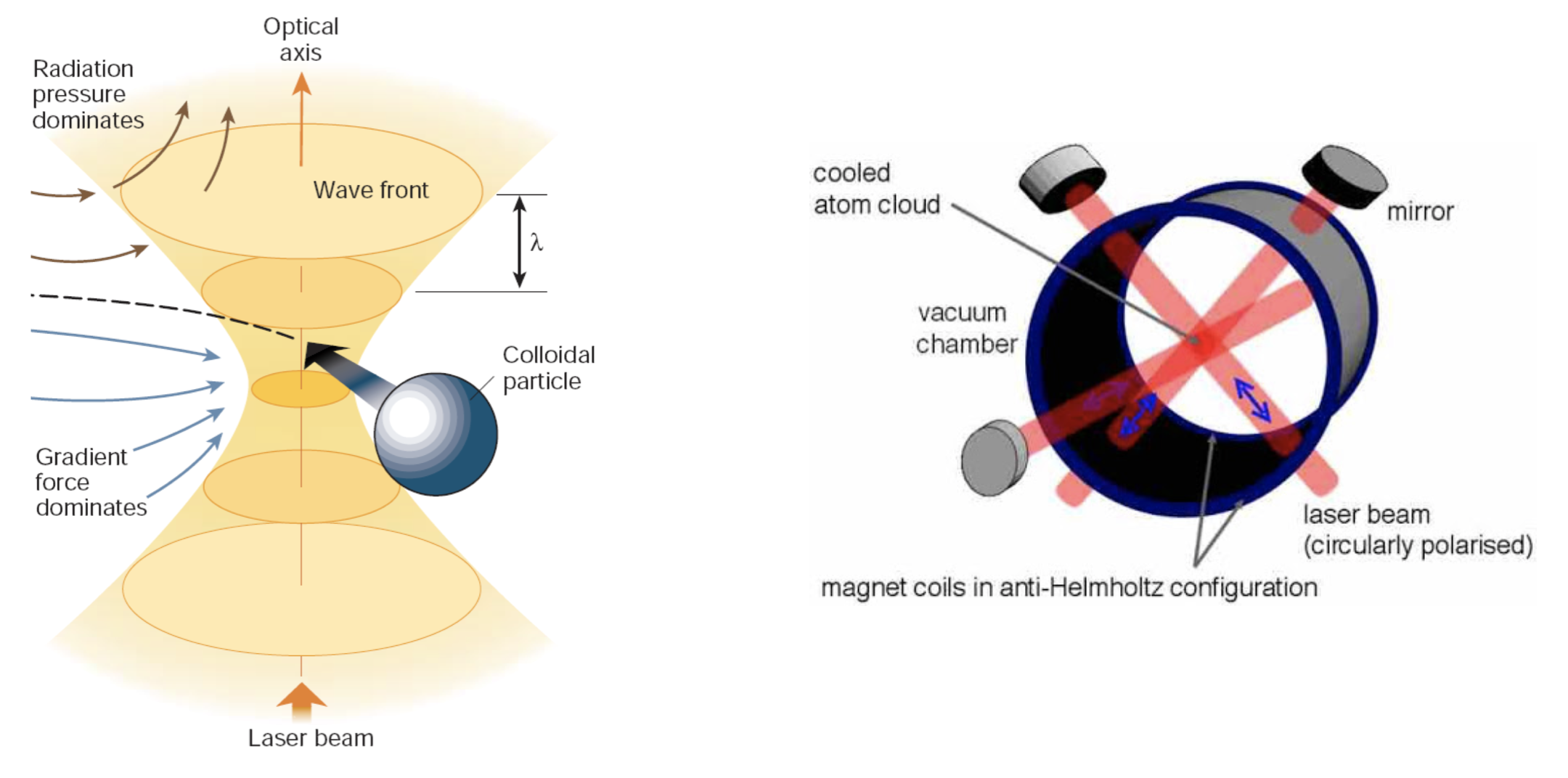

Radiation pressure has emerged as a crucial tool for manipulating both microscopic particles and atomic species. Figure 3 (left) illustrates optical tweezers, where a tightly focused laser beam traps colloidal particles. While radiation pressure tends to push particles along the beam direction, additional gradient forces arising from the intense light field’s spatial variation maintain the particle’s position in the focal region. This technique has become invaluable in biophysics for:

- Measuring piconewton forces generated by molecular motors

- Studying protein folding mechanisms

- Investigating enzymatic processes such as CRISPR/Cas gene editing

but also for fundamental physics

- like the measurement of the Casimir force

- understanding the interaction of light with matter

- and the measurement of the radiation pressure itself

- or even measuring the Maxwell Boltzmann distribution of single particles

At the atomic scale, radiation pressure combined with magnetic fields enables the trapping and cooling of atoms to temperatures of a few millikelvin in Magneto-Optical Traps (MOTs). Through additional cooling mechanisms, these atomic gases can reach even lower temperatures where they transition into a quantum state known as a Bose-Einstein condensate. This process relies on precise control of atomic hyperfine transitions.

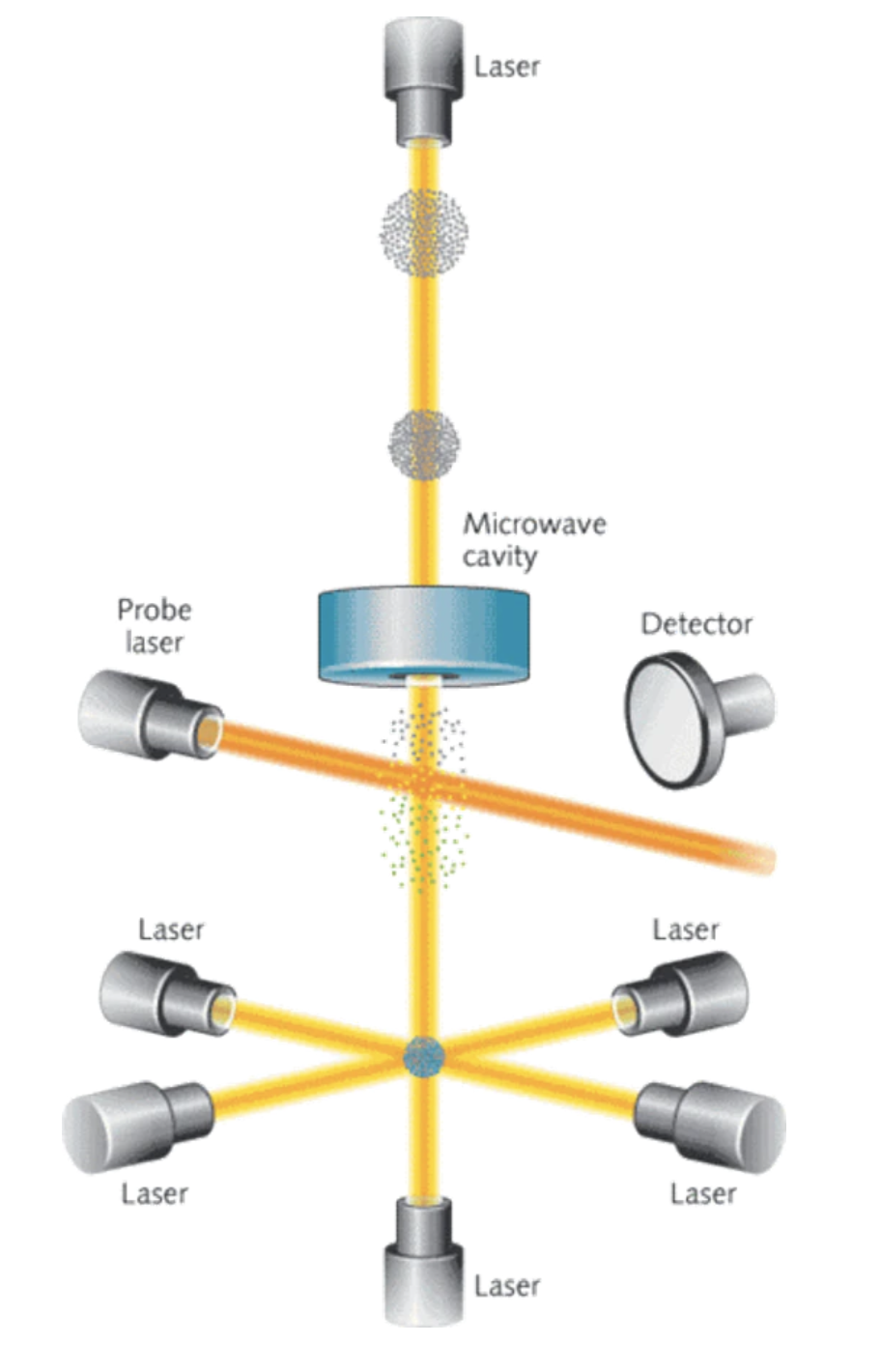

These atomic trapping techniques form the foundation of modern atomic clocks, essential for GPS navigation and gravitational wave detection. Figure 5 shows a fountain atomic clock design, where laser-cooled atoms are propelled upward through a microwave cavity by radiation pressure. Here, the atoms’ hyperfine energy levels interact with the microwave field.

In their fountain-like trajectory, atoms pass through the microwave cavity twice, enabling precise measurements of atomic transition frequencies. These measurements establish a fundamental time reference with unprecedented accuracy, used to synchronize timekeeping systems worldwide.